Vol 2 No 1 2008

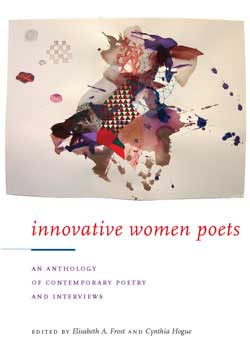

Innovative Women Poets: An Anthology

of Contemporary Poetry and Interviews Univ. of Iowa Press: Iowa City, 2007 Reviewed by Stacey Waite |

|

There is a sense, when a new poetry anthology appears, that the anthology itself is a kind of translation of the poets’ work—moving their poems from one context to another, one not invented by the poets themselves but by the parameters of the book itself. What is most valuable and, in fact, innovative about Elisabeth A. Frost’s and Cynthia Hogue’s Innovative Women Poets is that the anthology itself resists the very taxonomy that many anthologies depend on. Even as the poets anthologized in the collection (like Gloria Evangelina Anzuldua, Alice Notley, Alicia Ostriker, and Sonia Sanchez) are said to “trouble existing generic borders” (according to the editors’ introduction), Frost and Hogue also resist these same generic borders in the methodology behind this gathering of work. They resist, first, the power of naming that an anthology usually takes for granted. There are no sections, no headings, no linear timelines. The editors further explain that innovative poetry “can be defined in terms of both “formal attributes (work that challenges dominant artistic conventions) and cultural stance (speaking from, or about, the margins or borders of power).” This complicated understanding of innovation makes for a versatile and layered anthology, grouping together women poets (Barbara Guest, Harryette Mullen, C.D. Wright, as well as those mentioned above, to name a few of the fourteen poets who appear) influenced by or writing out of a variety of aesthetic movements in the latter half of the 20th century—including the Black Arts Movement, the New York School, and Feminist Poetry.

Innovative Women Poets offers its reader the significant project of reading poets one would not read side-by-side in any other anthology of its kind. One gets the sense that a conversation is happening not about these poets, but between them, both because their work defines and redefines political, creative, spiritual and personal innovation and because their own voices are at the forefront of the collection in the form of interviews—some of which were conducted for this volume and others that were edited and reprinted from other scholarly sources.

In Hogue’s interview with Alicia Ostriker, Ostriker remarks about her move from a Blakean scholar to a scholar of women’s poetry: “…you are so constricted in your expression when you’re writing a scholarly article. You can be witty but you can’t be playful, you can be passionate, you can’t be joyful or sorrowful or angry, you have to crayon inside the lines.” The interviews give each poet an opportunity to reclaim a measure of control over their work where the lens through which to view their poems is imposed though this does not boil down to something reductive like the writers’ intentions. The inclusion of both poetry and interviews gives the reader a multi-faceted understanding of each poet’s variety of invocation. Critical, playful, joyful, sorrowful, angry, these women surely do not crayon inside the lines.

This refusal to adhere to an artificial poetic or critical standard is felt not only as a political resistance but also as an act of survival, a literal refusal to be erased or to be erased by being understood in terms that seek to contain rather than open. I think it’s useful as a way of representing this anthology to turn to its ending, to the poems of Kathleen Fraser. In the final selection, after line upon line of repetition, she writes:

and

little tasks of pain had tried to lift |

as |

In this spirit, the poems in this collection have in common poetry as re-visionary in its form, its rhythms and cadences, and its political commentary or content when language is called into question. Here Fraser illustrates the reaching of language for itself, the very problem of making a sentence, or sentiment, or subject. The collection leaves open the interrogation of what counts as innovative or creative, and of course when it counts and for whom. As someone who has often been troubled by anthologies informed primarily by identity politics—anthologies that group poets by some stable sense of identity formation—I find Innovative Women Poets refreshing in its sense of identity as something “not static but frayed, layered, fettered, furling”—identity as both movement and a kind of imprisonment. In this sense this collection is more theoretically nuanced, more queered than many of the anthologies collected in the name of feminist studies or queer studies that have come before it.

In their introduction, Hogue and Frost articulate their hope that Innovative Women Poets can “foster discussion…about the radical shifting of poetic substance, of what is expressed and expressible.” This assertion not only brings our attention to one of the goals of the anthology, but it also positions the anthology in conversation with some of the most cutting edge and significant theoretical work being done in queer theory in order to help us re-imagine what is ‘expressed and expressible.’ For example, Judith Butler, in her most recent collection of essays, Undoing Gender, writes: “fantasy is part of the articulation of the possible; it moves us beyond what is merely actual and present into a realm of possibility, the not yet actualized or the not actualizable.” Butler’s understanding of fantasy and possibility, her imagining of a subject who can be moved ‘into a realm of possibility,’ is a perfect perspective from which to imagine reading, or even teaching from, an anthology likes this one. If what we want is to become readers who can notice or see beyond “what is merely actual or present,” if what we want is a more complicated and disruptive understanding of identity, if what we want is to imagine new ways of naming or not naming what we read and see, this anthology is certainly a place to begin—a place out of which we can all come unfurled, unfettered and thick with possibility.

Stacey Waite lives in Pennsylvania where she teaches courses in Composition, Queer Theory, Literature and Creative Writing. After receiving her MFA in poetry in 2002, Stacey has published two collections of poems: Choke (winner of the 2004 Frank O'Hara Prize in Poetry) and Love Poem to Androgyny (winner of the 2006 Main Street Rag Chapbook Competition). Her poems have been published most recently in Bloom, The Marlboro Review, Gulf Stream, Nimrod and Poet Lore. She has also published an article on literacy and consciousness in Feminist Teacher’s Spring 2007 issue. She is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Composition, Rhetoric, Literacy and Pedagogy at the University of Pittsburgh.